I visited the National Cryptologic Museum in Fort Meade, Maryland. It is run by the National Security Agency (NSA), the U.S. agency responsible for electronic spying and monitoring. Although most of the work they do is very secret, the museum is open to all, does not charge admission, and allows pictures.

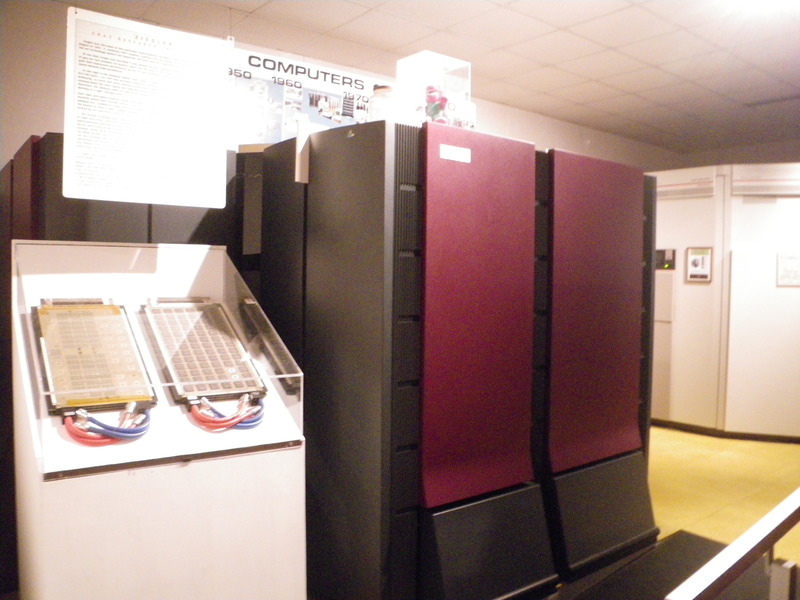

For me, one of the attractions of the museum is the old computers on display. It used to be (and may still be) that whatever the fastest computer was, the NSA would automatically buy one or more of them. These are old Cray supercomputers.

Part of the museum is devoted to U.S. military encryption systems through the decades from World War I.

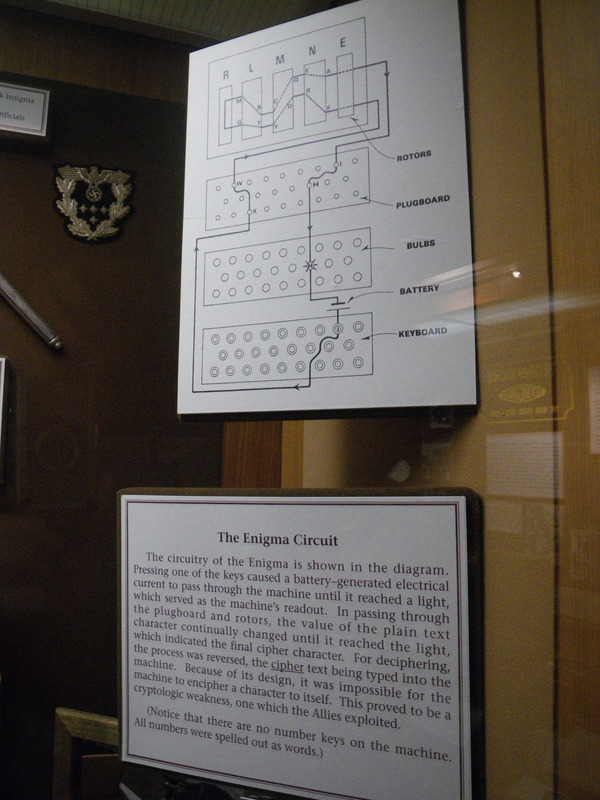

As the museum guide told us, the systems that successfully provide security aren't quite as interesting as the systems that fail to provide security. The part I most enjoyed about the museum was the Enigma machines, which were used by Germany during World War II to encrypt their communications, and which the Allied forces very frequently broke, thus gaining valuable intelligence.

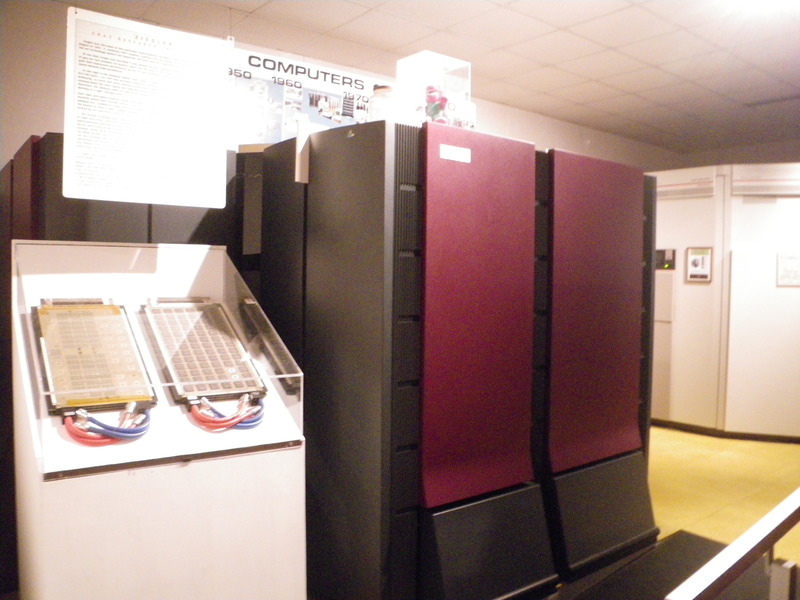

The enigma works by swapping pairs of letters of the alphabet, with the exact swaps determined by the wiring and position of three or four rotors, and the position of plugs in a plugboard. The position of each rotor changes every time a new letter is typed. Because the signal travels twice through the rotors, once right-to-left and then back from left to right, the same exact equipment and settings can be used to decrypt an encrypted message as to encrypt a message for transmission.

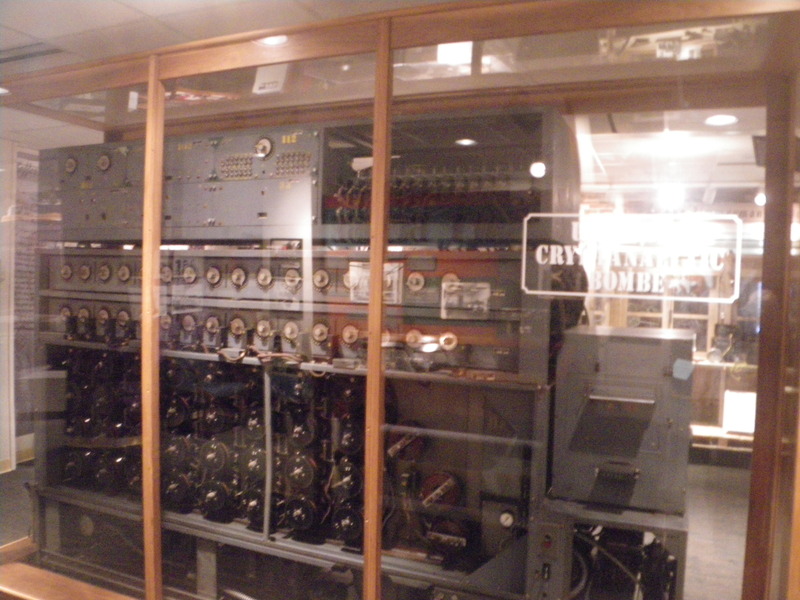

One of the reasons for my interest is that some of the early famous people in the history of computing, and particularly Alan Turing, were involved in building the machines that regularly found the Enigma settings that the Germans were using on a particular day. These machines were in some ways the forerunners of modern computers.

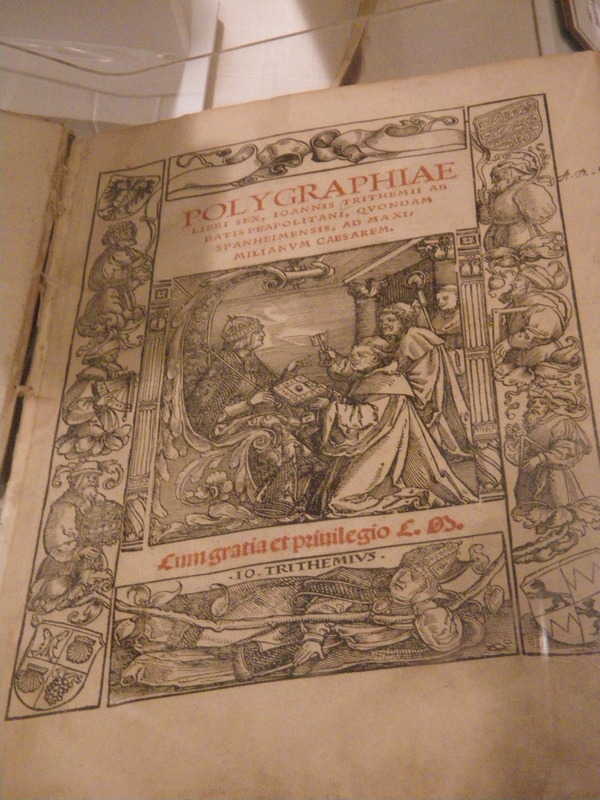

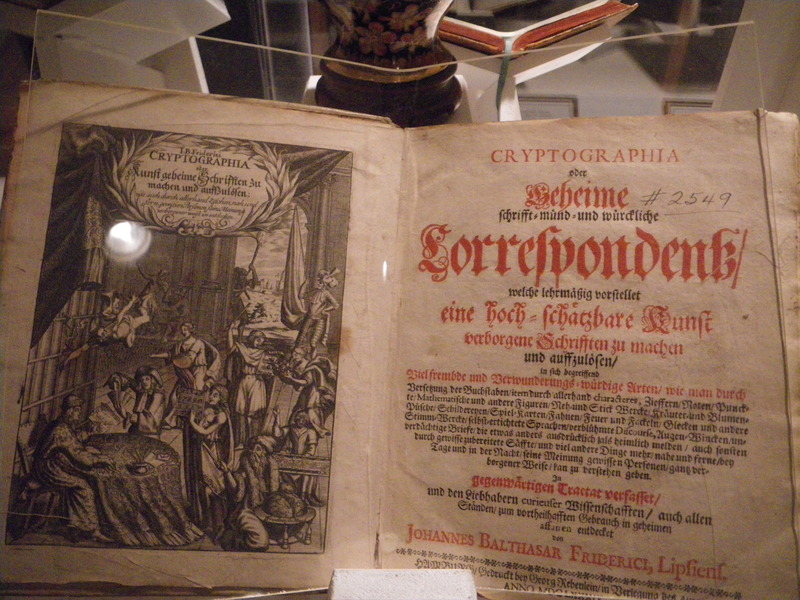

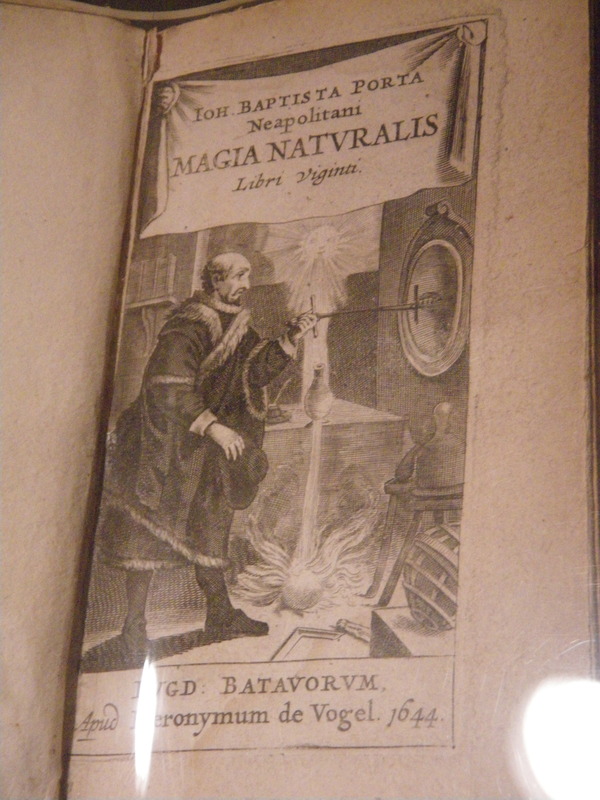

The museum includes other historical exhibits, including hand-powered encryption devices.

The museum also includes examples of historically difficult decyphering problems. This is a copy of the Rosetta stone, which was originally written (over 2,000 years ago) in Egyptian hieroglyphs, demotic Egyptian, and Greek. It was rediscovered in 1799, and finally deciphered in 1822, giving the first key for reading Egyptian hieroglyphs.