Lake Butrint is a coastal lake in the Southern part of Albania, connected to the sea by the 2km Vivari channel. The channel goes through a low area between two sets of hills, allowing the water to flow both ways, and in consequence the water Lake Butrint is a mix of freshwater and saltwater. Because of this, the lake has many different kinds of fish.

The first picture shows the lake, and the next few pictures the channel. The opening of the channel into the sea is generally considered the boundary between the Ionian sea and the Adriatic sea.

Less than two kilometers across the sea is the Greek island of Corfu. This picture shows the Albanian mainland on the left, and Corfu on the right.

Locations around the lake have been settled since the prehistoric times. On the North side of the Vivari channel is a little hill surrounded on three sides by the lake, only connected to the mainland by a narrow isthums to the West. This strategic location has been settled since at least greek times, when it was known as Bouthroton. Roman writers wrote that it was founded by Helenus, a refugee from Troy. Virgil wrote that Aeneas stopped in Bouthroton in his wanderings which eventually led to the founding of Rome.

The greek city was built in the flat area between the hill and the channel, and included temples and a theater, which was later adapted by the Romans. Like other cities built on alluvial soil, particularly Venice, the city is built on land that is slowly sinking, approximately a meter every thousand years. Some of the ancient city is now underwater.

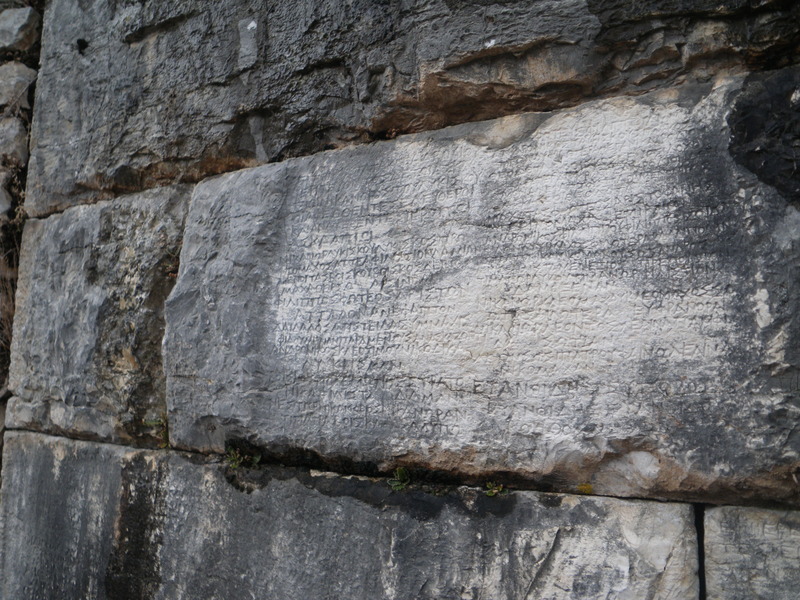

Some of the stones in the temple of Asclepius record the names of slaves freed in Asclepius's name.

As is true for the rest of the Mediterranean, eventually Bouthroton became part of the Roman empire, renamed Buthrotum. Cicero's friend Atticus had a villa on lake Butrint, and objected to plans to settle Roman veterans in the area. By the end of the Roman period, Buthrotum had many temples, an aqueduct, a forum, and baths. The next picture shows part of a Roman bath, followed by pictures of several small temples next to the forum.

The main hill of Buthrotum was fortified with walls and mighty gates. The lion gate has a sculpture of a lion killing a bull. At another gate, it is still possible to see the stones on which the sentries stood, The sentries' footprints are worn into the rock.

Eventually, like the rest of the Roman empire, Buthrotum became Christian. The next pictures show the remains of a big rectangular building and a nearby circular building. The rectangular building is a basilica, used as a major church. The circular building is a baptistery, used for baptizing people. The small opening in the center of the baptistery used to hold holy water, and is where people were actually baptised.

The floors of both the basilica and the baptistery have impressive mosaics, but to protect these from the sun, they have been covered with sand, except in one corner of the basilica.

Over the centuries after the Roman empire collapsed, Buthrotum changed hands several times, being conquered or sometimes purchased by the Bulgarians, the Byzantines, the Venetians, and the Ottoman Turks. In 1797 it was assigned to France, and in 1799 it reverted to Ottoman control, though the local governor, Ali Pasha Tepelena, was allied at times with Napoleon, and at times with Great Britain. This is the same Ali Pasha named in "The Count of Montecristo" as the father of the mysterious, exotic, and beautiful slave Haydee that the Count always travels with. Throughout his imprisonment and adventures the count always loved Mercedes, whom he would have married had he not been imprisoned. By the end of the novel the Count has realized that she will never be his, and instead, he leaves with Haydee, who also loves him.

While the Count of Monte Cristo, Mercedes, and Haydee are all fictional, Ali Pasha Tepelena is a historical figure. Here is his statue in the little town of Tepeleni, where he was born.

Ali Pasha Tepelena lived during dangerous times, and defended his dominion not only with strategic alliances, but also with mighty forts. Like the Romans and the Venetians, he fortified the top of the hill of Butrint. I am not completely sure to which period each of these walls and forts belong, but together they show how well fortified Butrint was. The first few pictures show the part of the lake that is to the North of the peninsula, and the last few show the West side and the little isthmus connecting Butrint to the mainland.

The North side of lake Butrint is a flat swampy area, and was malarial in the 19th and 20th centuries. During the communist period, the swamp was drained by digging a canal through some hills, not far from the coastal city of Saranda.

Like Mongolia, Albania seems to have moved on from its Communist past. Unlike Mongolia, Albania had a chaotic period leading up to World War II, in which Italy played a substantial part. During World War II, Albania was occupied by Italian forces under the government of Mussolini, then by German forces after the Italian surrender in 1943.

I have seen in old museums communists claims that from 1943 the partisans under Enver Hoxha gloriously defeated the German occupying forces, though I have a slight suspicion that other factors might also have played a role in the eventual German withdrawal from Albania.

Enver Hoxha (the "xh" pronounced as the last consonant in the French word "garage") went on to become a brutal dictator on the model of Stalin. He shifted alliances multiple times over the years, to keep Albania from becoming a dependency of Marshal Tito's Yugoslavia. The end result was that Albania became substantially isolated from the rest of the world.

Under the Ottoman empire, Muslims paid lower taxes than Christians, and many Albanians became Muslim. The communist regime strongly endorsed atheism and destroyed some churches and religious artwork. The Albanian state no longer takes a position on religion, but it is my understanding that a majority of Albanians are still atheists. Of those who are not, Muslims and Christians live side by side in peace. Likewise, it is my understanding that the minority Greek population lives side by side in peace with the Albanian majority.

Modern Albania is fairly well integrated into the world economy, though it is hard to exchange currencies into Albanian Lek anywhere outside of Albania, as I found Mongolia's Togrog hard to purchase outside Mongolia.

As is true of many of the less wealthy countries in Eastern Europe, many younger Albanians migrate elsewhere in seach of better economic opportunities. Albanians have been migrating for centuries, though. A population of Albanians settled in Southern Italy as early as the 1400s, with greater numbers migrating to escape the Ottoman occupation. These populations, known as the Arbereshe, still speak an older form of the Albanian language.